Even if you’ve never watched the show Mad Men, you’ve probably heard the phrase “It’s toasted.”

“It’s toasted” features as the climax of the very first episode of Mad Men, in a scene that captured attention and sparked the show’s runaway success. It’s also a real tagline for Lucky Strikes cigarettes, adopted by the brand in 1917.

In episode one, ad-man Don Draper struggles with a seemingly insurmountable problem. Mad Men is set in the 1960, and the latest research on cigarettes has just been released.

Spoiler alert: it’s not good. Draper’s job is to sell cigarettes anyway.

The climax of the episode showcases Draper’s marketing and copywriting brilliance, as he seemingly pulls “it’s toasted” out of thin air.

But what makes Mad Men, and Don Draper, so brilliant is that this final moment of discovering the tagline is foreshadowed throughout the entire episode.

A close watching of season one, episode one reveals that the show’s creators crafted a subtle build-up to the climax.

Inspired by David Ogilvy’s Confessions of an Advertising Man, the show highlights moments crucial to the copywriting and advertising process—behind the scenes work of customer research and positioning.

Mad Men creator Matthew Weiner was inspired by David Ogilvy’s well-known book (Source, Amazon)

Mad Men ran for 7 seasons, and it’s packed full of marketing wisdom. I recently sat down to rewatch the first episode, then immediately paused to start taking notes. The doc ended up around 1500 words.

Here are the Mad Men marketing lessons from just one episode.

- Use the words your audience uses

- List all the features of your product

- Sometimes coupons are a bad idea

- Avoid arguments you can’t win

Don Draper struggles to sell tobacco, so he tries a classic advertising technique

Opening shot. The camera pans through a crowded restaurant. People talk indistinctly, voices blending together into a murmur. The shot finds its way to Don Draper, fiddling with a cigarette, pen, and napkin. He’s alone.

We don’t quite know it yet, but Don Draper has a problem: smoking kills, and he’s been hired to sell cigarettes. How do you write an ad for a product that literally causes cancer?

The opening scene is 2 minutes and 29 seconds long. You can watch it on YouTube. Despite its length, it jams in enough marketing insight that I was typing furiously.

Mad Men marketing lesson one: Use the words your audience uses

He asks his server for a light, then strikes up a conversation about cigarettes.

“What brand do you smoke,” “Why did you start smoking,” “Is there anything I could do to get you to switch brands.” Those are the kinds of questions Draper asks. Sounds oddly similar to a market research survey, right?

And Draper gets answers. He learns that the server

- Started smoking when he was given free cigarettes in the military, and has smoked the same brand ever since

- Hasn’t ever considered switching cigarette brands

- Has heard that cigarettes are dangerous (from his wife) but dismisses it because…

- He loves smoking. He comments that if his preferred brand disappeared, he would still find something to smoke

This last comment makes Draper perk up a bit. When the server says “I love smoking,” he mutters to himself, “I love smoking, that’s very good.” And then writes it on his napkin.

What’s going on here?

Don Draper is doing customer research. In the field.

Legendary copywriter Eugene Schwartz once remarked “There is your audience. There is the language. There are the words that they use.”

There is your audience. There is the language. There are the words that they use. – Eugene Schwartz Tweet this!David Ogilvy, in many ways the inspiration for Don Draper, once remarked:

“I don’t know the rules of grammar…If you’re trying to persuade people to do something, or buy something, it seems to me you should use their language, the language they use every day, the language in which they think. We try to write in the vernacular.”

Modern copywriters have taken this to heart as well. The school of “conversion” copywriting, pioneered by Joanna Wiebe, applies wisdom from the old masters to modern products and marketing mediums.

When Draper says “that’s very good,” he’s thinking that he’s just found a piece of “swipe-able” language. Language that he might be able to use in an ad.

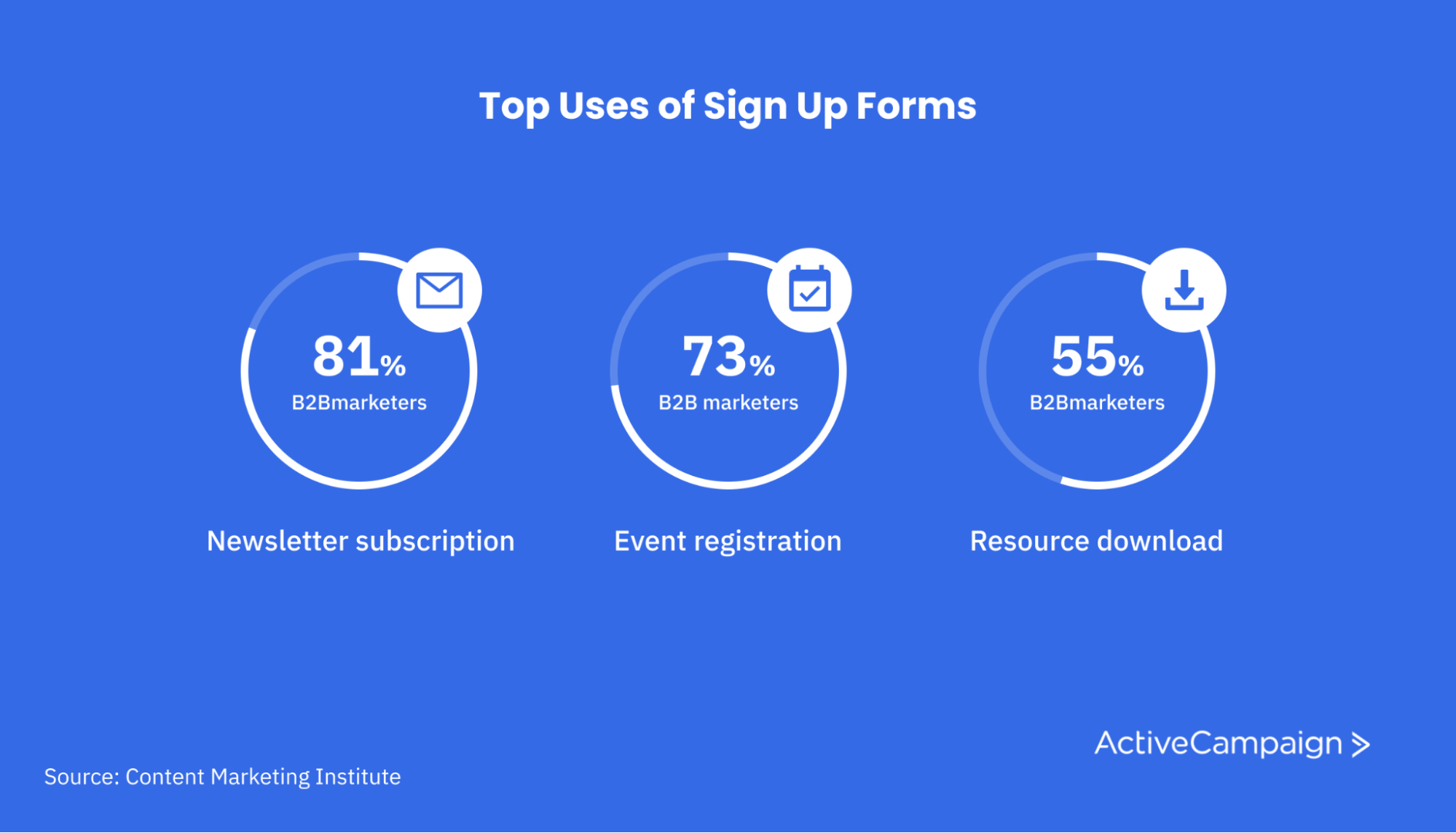

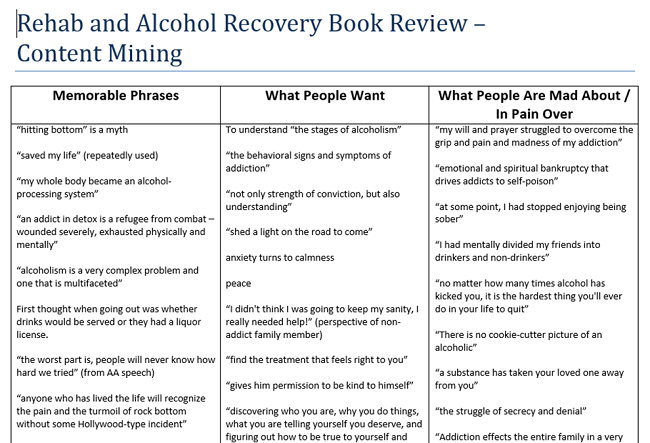

An example of how copywriter Joanna Wiebe organizes her customer language research. The copy that came from this research increased clicks by 400%. (Source, Copy Hackers)

It’s worth noting also that Draper is actually smoking Lucky Strikes in this opening sequence. This is another important piece of research, which we see more of in the next scene.

The master feature list, “crushproof box” included

A scene-by-scene analysis of episode one is overkill, so let’s cut to the heart of the next scene.

Draper goes to get help. And here, for the first time, we learn the problem.

Advertisements for cigarettes are no longer allowed to make health claims or downplay the risks of smoking. Draper runs through a list of cigarette features that he’s no longer allowed to use (things like filtered tips and low-nicotine).

At the end, he winds up with just one feature remaining: crushproof box.

Obviously, crushproof box isn’t much of a selling point. But this valuable lesson of this scene is not that Draper has a breakthrough—it’s that he’s using classic copywriting techniques and not getting a breakthrough.

Mad Men marketing lesson two: list all the features of your product

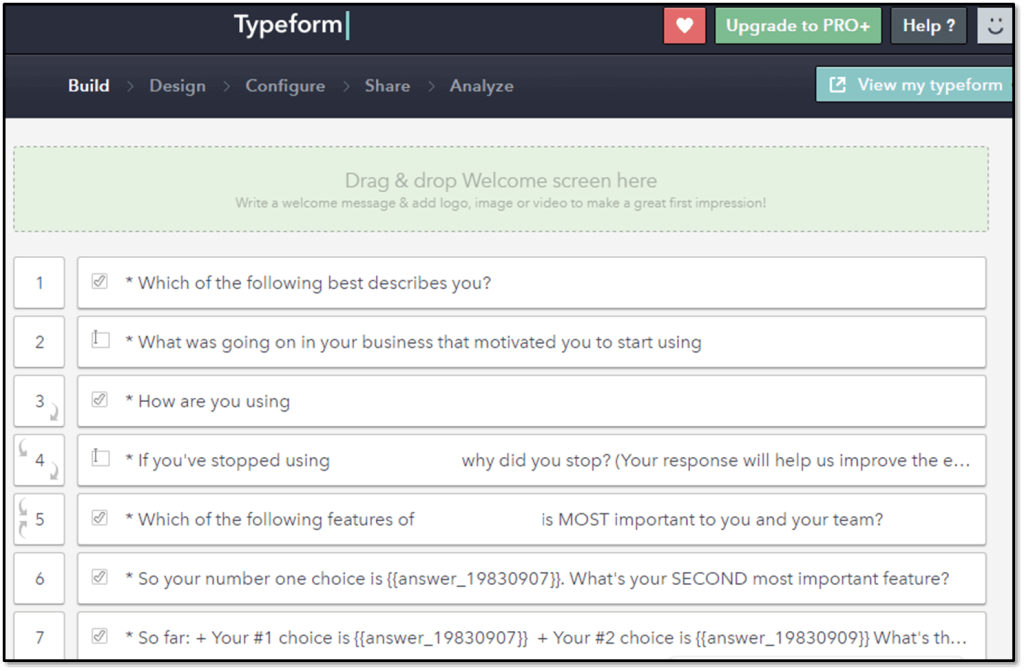

Modern conversion copywriters like Joanna Wiebe and Joel Klettke write out a list (well, spreadsheet) with every feature of the product they’re trying to sell.

Ultimately, the goal is probably to sell prospects on benefits rather than features. But putting together this master feature list and mapping the features to benefits is a valuable research step—it surfaces insights and connections that you may not have otherwise considered.

After you’ve listed out all the features, you can do a survey to figure out which ones to emphasize in your copy. This example comes from Joel Klettke. (Source, Business Casual Copywriting)

That’s what Draper is trying to do here. He’s listed out every feature he can think of for a cigarette. He’s looking for something new, something he might have missed. Something compelling enough to overcome the fact that smoking kills.

He just doesn’t find it. Yet.

An instructional detour

From here the episode begins to set up plotlines for later in the season. We’re introduced to Ms. Mencken, who runs a series of Jewish department stores. Draper delivers a few memorable burns to junior executive Pete Campbell.

There’s some conversation about cigarettes, and the Sterling-Cooper research team comes back to Draper with research that ultimately proves unhelpful. Draper’s feedback: the issue isn’t getting people to smoke. It’s getting people to smoke Lucky Strikes.

The most important lessons in this interesting detour come from the client meeting with Ms. Mencken. Draper and Sterling lay out a simple strategy to increase the profile of Ms. Mencken’s department stores

- Begin with a general awareness campaign, targeting specific shows

- Offer a 10% off coupon in select ladies magazines to increase first time visitors

This is a time-honored approach to sales and customers.

It’s so time-honored, in fact, that copywriter Claude Hopkins wrote about it all the way back in 1923, in his still-useful text Scientific Advertising.

This this is almost 100 years old, and it’s still gold (Source, Amazon)

When Ms. Mencken isn’t convinced, Draper says simply: “Ms. Mencken, coupons work.”

Mad Men marketing lesson three: Sometimes coupons are a bad idea

The client isn’t convinced. And she has a good argument.

When Draper asserts that “housewives love coupons,” Ms. Mencken changes the conversation. As she says, she wants “people who don’t care about coupons, whether or not they can afford it. People who come to the store because it is expensive.”

This is an interesting approach that goes against a lot of common thinking. It also has a lot of merit.

Cultivating an image of luxury and exclusivity activates some powerful psychology. It activates scarcity, because relatively few people can afford expensive products. It offers social proof—wearing expensive products is a signal of status.

This episode, with its focus on cigarettes, spends relatively less time on the debate of cost vs. luxury. Still, it’s an interesting debate worth reading more about. The Luxury Strategy, by Jean-Noël Kapferer and Vincent Bastien, is a useful read for many businesses.

The grand finale: It’s toasted

Detours behind us, the episode reaches its climax. The agency has a meeting with Lucky Strike cigarettes, and Don Draper still doesn’t have any ideas.

As you might expect, the meeting starts out poorly.

The Lucky Strikes people come in expecting brilliance, and there is precious little brilliance to be found. Voices are raised. Bad ideas are shot down. The client is about to walk, and then…

All of his research pays off, and Draper finds the answer.

He starts out speaking softly. He voices a key insight—everyone else’s cigarettes cause cancer too. Every other cigarette company is facing the same problem as Lucky Strikes.

It doesn’t make sense to argue that cigarettes are healthy. The best argument anyone could make is that the health risks are overblown—which is still an acknowledgement that they exist.

Arguing about the health of cigarettes was a “red ocean.” It was a point that everyone was going to be fighting over. A crowded space. Not a good place to be in marketing.

Mad Men marketing lesson four: Avoid arguments you can’t win

Draper’s core insight is that Lucky Strikes should drop the health risk conversation altogether. Don’t bother fighting a vicious, losing battle. Instead, move to a blue ocean—a place without any competition.

Draper’s epiphany also builds on an idea from early in the episode —people love smoking. What does that mean?

- People want to smoke—but they don’t want to feel guilty about doing something unhealthy. They’ll try to convince themselves that smoking is ok, because they love it.

- If you don’t call attention to health risks, people will avoid thinking about them (because they don’t want to think about them)

- You can imply health or high quality without explicitly talking about it. “It’s toasted” isn’t a health claim—but it does create the sense of a “natural” product.

There’s an important point here that’s easy to overlook. Draper doesn’t actually come up with the phrase “it’s toasted” on his own. Instead, he asks the owner of Lucky Strikes to describe how they make their tobacco.

“We breed insect-repellent tobacco seeds, plant ‘em in the North Carolina sunshine. Grow it. Cut it. Cure it. Toast it—”

And Draper interrupts with “there ya go.” And then he says “everyone else’s tobacco is poisonous. Lucky Strikes is toasted.”

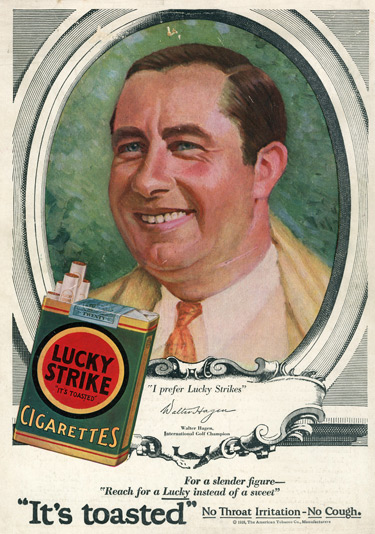

This is a real ad for Lucky Strike. In real life, the slogan started use in 1917 (Source, Stanford)

He goes on to say that all people really want is to feel that what they are doing is ok. People want to smoke. Advertising that tells people it’s ok to smoke, even in the face of health risks, would sell cigarettes.

This final revelation is the culmination of the entire episode.

- The server who said that he loves smoking

- His mistress, who says not to worry because people love to smoke

- Draper’s own response to internal Sterling-Cooper research (the goal isn’t to get people to smoke, but to smoke Lucky Strikes)

- The idea of a master list of features (“it’s toasted” is really just a different type of feature)

And, ultimately, the winning tagline doesn’t even come from Draper himself. It comes from natural, simple language. “Plant ‘em in the North Carolina sunshine. Grow it. Cut it. Cure it. Toast it.” That whole sentence could be copy for an advertisement.

The end result of all this research? “It’s toasted.”

Conclusion: The construction of a great ad

The real-life slogan “it’s toasted” wasn’t created to combat the health risks of cigarettes. And, in real life, it’s a little unsettling to think of all the research and brilliance that goes into selling unhealthy products.

Still, this first episode of Mad Men is packed with marketing and advertising brilliance. If you look in the right places, it’s easy to see that the showrunners took the lessons in Confessions of an Advertising Man to heart.

(Is advertising like Mad Men? If you sit in a creative meeting at a modern ad agency, you’ll find that it can be surprisingly similar! Minus the whiskey.)

The takeaway? Great advertising can come from brilliance, but brilliance ultimately comes from research.